What is diacetyl?

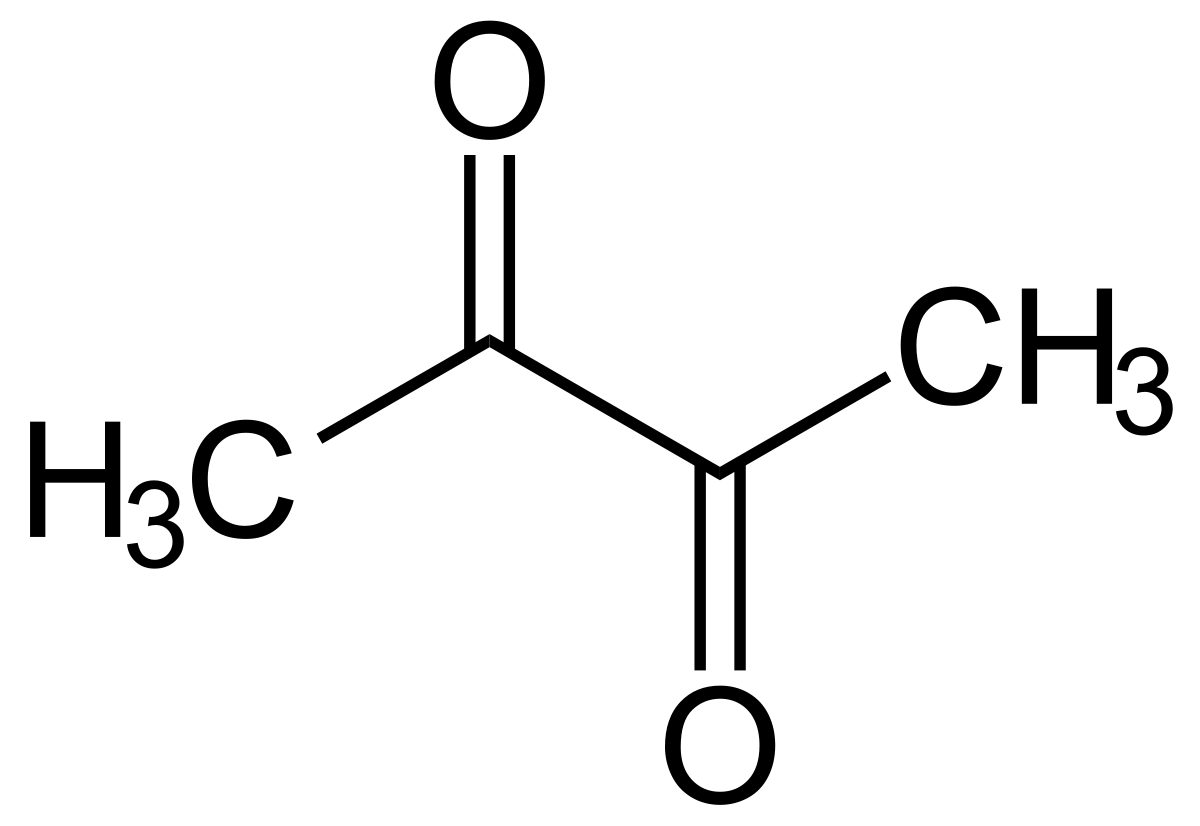

For yeast cells to grow they need nutrients, some for energy and some to build new cell material to enable multiplication. That which they cannot draw from the wort, the yeast needs to synthesise from simpler starting materials. During the synthesis of the amino acid valine, a by-product is diacetyl.

The challenge with diacetyl is that it has a low taste threshold and it tastes of butterscotch, not a flavour we want in most beers.

How is diacetyl formed?

It is good to understand this, as it underpins how the diacetyl test works. As with most biochemical pathways, the formation of diacetyl is a multi-stage process. It is important to understand that up until the penultimate stage these steps are enzyme catalysed (i.e. fast) but the final step from α-acetolactate (AAL) to diacetyl is a simple but slow chemical reaction. With AAL being capable of being formed faster than it is consumed, a residual concentration can build up in the final stages of fermentation. This is especially true in lower temperature fermentations. Thus once your ale / lager has reached its terminal gravity it may not taste of diacetyl, but if AAL is present, it will be formed with time in the final package. Thankfully yeast also contains an enzyme which will reduce diacetyl to 2,3-butandiol which has a far higher taste threshold and this eliminates the off flavour issue. Thus the diacetyl rest, a period of warm conditioning at the end of fermentation, which allows the AAL to convert to diacetyl and under conditions where it can be consumed to form something essentially flavourless. Cool down the green beer and this enzyme cannot act.

So what is a diacetyl test and how to I perform it?

You could take a sample of your green beer and inject it into an HPLC and see if AAL is still present, but if you don’t have a spare £25k burning a hole in your pocket there is a far simpler and cheaper method:

Take two samples of your green beer, 50 ml each is enough, into sealed bottles. Place one into the fridge (the control) and drop the other into a jug of hot water at 60-70 C, chances are you have some hot liquor to hand which would be ideal for this. Leave the sample in the hot water for 20 min then remove and cool. Then all you need to do is to taste both samples.

- Can you taste butterscotch in the heated sample (having the control sample to compare against makes this assessment much easier) – If you can then you have some AAL still present in your green beer which will form diacetyl with time. The green beer needs longer to warm condition so hold at 16-20 C for another 24-48 hours and then run the test again.

- There is no diacetyl taste to either sample – your beer is ready to chill and move forwards.

My experience

Residual AAL / diacetyl is present at the end of the primary fermentation of some recipes but not all. The key factors are the choice of yeast, malt bill and fermentation temperature. Some combinations will require a diacetyl rest, some will not. Some craft breweries are paranoid about diacetyl in their beer and warm condition all their batches, but unless you are making a lager, this is an unnecessary loss of brewery efficiency. When you are running a new recipe then run the test for the first three gyles. If the test comes out negative at the end of each primary fermentation then unless you change anything it always will. Carry out warm maturation only on the beers which need it. Beer design is, in part, an art but its manufacture is certainly a science.

If you find yourself with a beer design where AAL / diacetyl is present at the end of the primary fermentation you do have another option. That is to add an exogenous enzyme (AAL decarboxylase / ALDC ) into your FV at the start of fermentation to guarantee that all the AAL will be quickly reduced to acetoin and no diacetyl will ever be formed.

Would you like help with the consistency of your beer quality? If so give me a call and we could arrange a phone / video consultation or if you are local I could come out and help you in person.