In this final post on whisky wash process optimisation I will cover the mechanical changes I advised and helped to implement with the new craft whisky distillery whom I have been supporting.

By inspection when I started with this client it was clear that just a handful of minor equipment changes should be able to greatly reduce their process time and with this, for the reasons I highlighted in my first post, significantly boost their yield from malt to sugar.

-

Swap out their heat exchanger (HX) for one with a larger surface area

-

Install pipework to allow for recirculation of the mash tun

-

Install pipework to allow for the recirculation of the hot liquor tank

-

Add inline temperature measurement between the HX the fermenters (FV’s)

None of the above issues stopped us making good quality wash, but the time required to make a batch when I started was around 8-9 hours which is far too long for whisky wash where you need active enzymes from the malt to survive into the fermenter to enable full fermentation and thus maximal yield.

Step 1 – upgrade the heat exchanger

Sadly the heat exchanger which had been installed had not been correctly sized and was simply not capable of cooling the wort from 64-67 C down to the required 25-28 C for fermentation. A quick fix to this was in place when I arrived, in the form of a copper coil in the underback, but this required the wort to be cooled batch-wise to 40 C before it could be pumped through the HX and hit the desired fermentation temperature. This was adding hours to the process time. Through my contacts I was able to get sizing data and source a pre-loved plate HX from a brewery in Essex to enable the wort can be cooled in one pass.

Step 2 – adding recirculation to the mash tun and hot liquor tank (HLT).

I still remember the guiding words my first Head Brewer gave to me when I started my brewing apprenticeship. He said “The two most important aspects of brewing are cleanliness and temperature control.” Simple advice which I now pass onto anyone that I train. Whilst I found a manual way to mix the HLT in the early days of this project, having recirculation yields an even temperature across the HLT, an important consequence of which is be able to get an accurate measurement of the mash water. Together this means hitting out mash temperature +/- 0.5 C for every batch now This really matters both to yield, quality and process time. With a whisky mash you start running off just as soon as you know the starch conversion is ‘complete’ which is determined using an iodine test. The sooner the starch is converted the sooner you can start running off the strong worts. Achieving the desired mash temperature every time clearly helps.

When I started there was no recirculation facility on the mash tun either, which made this a two man operation with buckets. This is great for your biceps, but is slower and less effective at producing a clear wash than a steady pumped recirculation flow. And as Bradley Wiggins proved in the 2012 Tour de France, winning a race is often about making a lot of small gains, which when added together become significant enough to put you out in front. In addition the manual recirculation method really requires two people, and wash preparation should really be a single person operation.

Step 3 – adding in-line temperature measurement on the chilled wash line

The final change required to make this a single person operation was to add in-line temperature measurement for the chilled wash. Early on, one of us controlled the wash / cooling water flow rates whilst the other monitored the temperature of the wash entering the FV with a thermocouple. Perfectly accurate, but again an unnecessary use of manpower and thus extra cost.

Final position.

Together these changes have reduced the batch time by a massive three hours. The rate limiting step is now getting the HLT for third water up to temperature in time. There is now time for one person to set up a distillation at the start of the day, move over to brewing a batch of wash with time left within a normal working day to shut down and wash the pot ale out of the still, leaving it ready it for the next day.

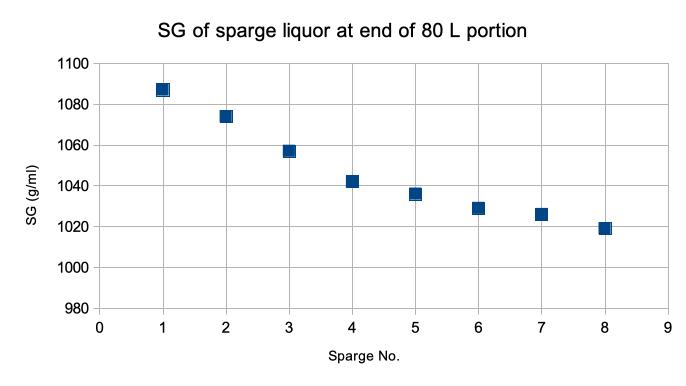

Before optimising the mash temperature and introducing third water we were seeing brewhouse yields of around 70%. Now they are consistently above 95%. In parallel, the manual effort and man hours of input to achieve this have been grossly reduced since the start of the project. A very satisfying result for everyone.

That completes my three posts on the project to define and optimise a new craft whisky wash process.

Post 1 – The key differences between beer wort and whisky wash manufacture

Post 2 – How process parameters were determined and yield optimised.

This post – How minor equipment changes significantly reduced the batch time.

If you would like help starting a new micro-brewery or distillery, or if you have an existing operation you would like to to optimise wrt time or yield and you are based in the North of England then give me a call.

Mash temperature

Mash temperature