I still remember the advice given to me by my first head brewer. “The two most important aspects of brewing” he said, “are cleanliness and temperature control.”

There are three classes of soiling you need to deal with in a brewery:

-

Organic soiling – that could be burnt on carbohydrates / proteins on the hot side and yeast residues in your fermenter

-

Inorganic soiling – this would be mostly scale (calcium / magnesium oxide) or calcium oxalate.

-

Biofilms – these tend to form in places where liquor can lie and which don’t see turbulent flow. Under the plates in the mash tun and in wort transfer lines for example.

Organic soiling

The most frequent / routine soiling you’ll be dealing with is organic soiling in the copper and your fermenters. You want to free this off of the vessel walls and then ensure it remains suspended until you can flush it out. The best cleaning agent for organic soils is specially formulated caustic (NaOH) solution. Brewery caustic formulations come with surface active agents in them to improve wetting, sequest metal ions and keen non water soluble soils suspended.

Your CIP caustic solution should be 1-3% NaOH (normally the concentrate is 30% NaOH). Take care with the concentrate and follow your local risk assessment. Googles and gloves are required and always add caustic to water, not water to caustic to avoid it overheating and spitting.

If you are a micro brewery you will not use huge volumes of caustic and it’s worth being aware that you can usually buy something suitable from your local agricultural merchants as it is also used to clean dairy milk tanks. Take care though as dairies tend to prefer formulations that also contain hypochlorite. Evans Vanodine CIP liquid would be a good choice because it contains no chlorine based chemicals.

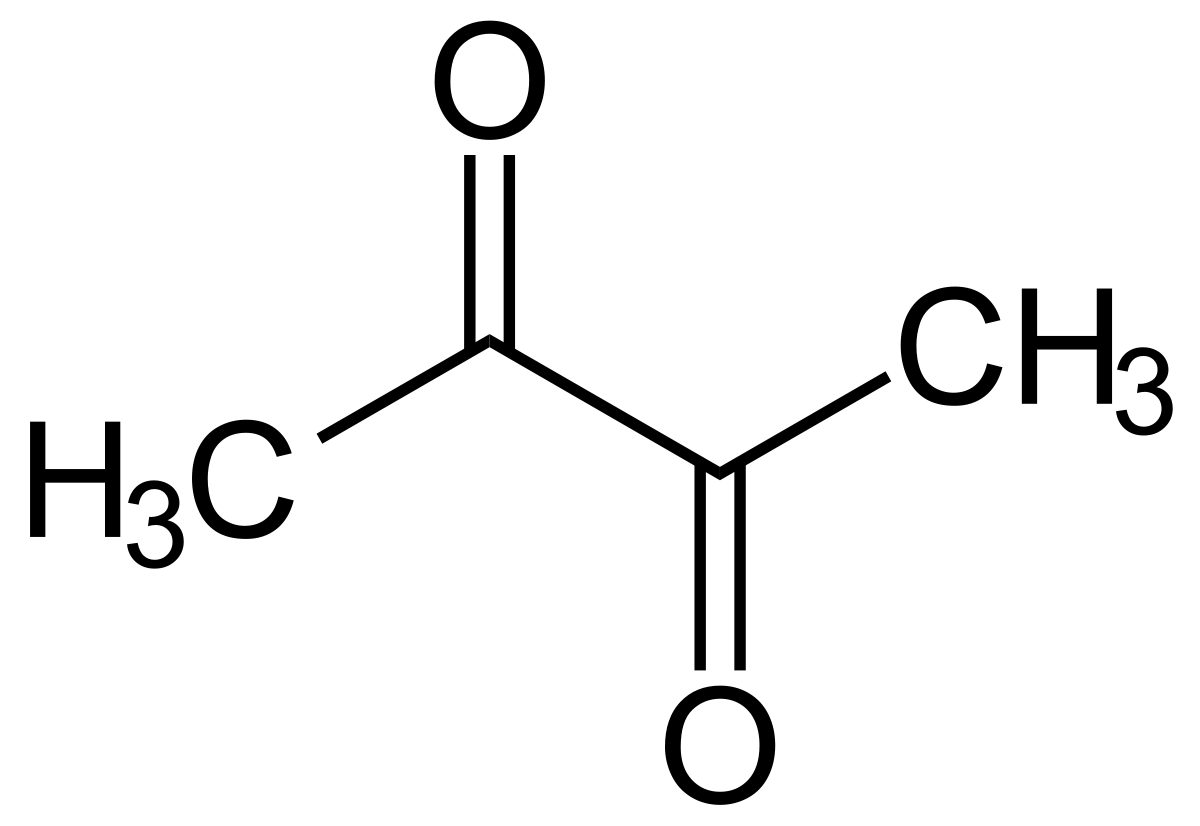

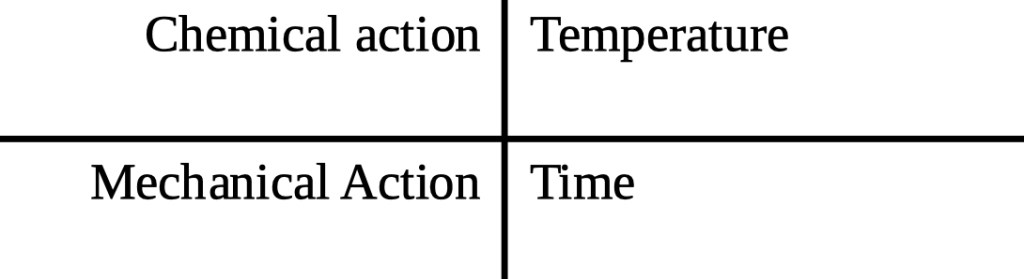

Different places where I have worked have had different protocols for the cleaning, but be aware that caustic cleaning is most effective at 50-80 C, needs to be recirculated for 15-20 min and should impact on your surfaces at > 1 m/s to guarantee turbulent flow. Why is there an upper limit you may wonder? That is to avoid baking your solids onto the heated surfaces. Here it’s worth mentioning the Sinner diagram:

You need all these factors to clean equipment, and if you reduce one (say chemical strength) you will need to increase one or more of the others (time, temperature or mechanical action). Once your vessel is free of soil you need to flush the caustic out as you definitely don’t want caustic in your beer. Simple phenolphthalein test papers work well to check the flush water.

With the base of your mash tun (below the plates) it is likely that you’ll not be able to use a spray ball system so you are probably looking at more mechanical action. Jumping into the vessel with a bucket and scourer or using a pressure washer! However this will probably only be necessary 2-4 times a year. This is a vessel entry, so again follow your local risk assessment. Actions should include, locking off any mechanical, chemical or heat inputs that you have and ventilating well.

Often a cold caustic cycle is all that is needed on the fermenter.

Cleaning fermenters – a cautionary tale

After you have transferred the beer from your fermenter there will be a high level of carbon dioxide with it. If you don’t already know, be aware that carbon dioxide reacts with caustic:

CO2(g)+ 2 NaOH(aq) → Na2CO3(aq) + H2O(l)

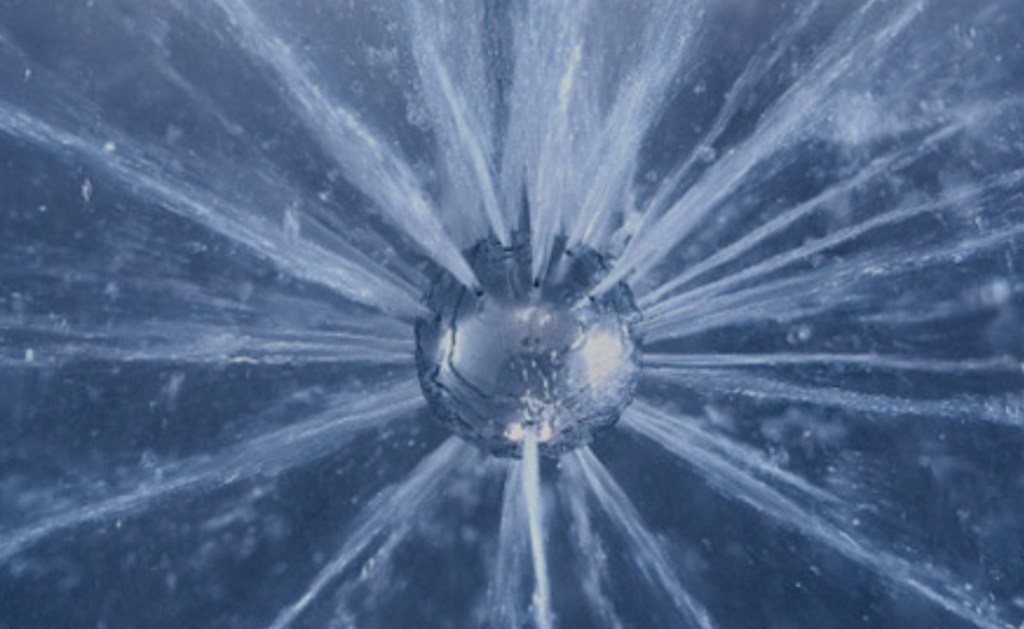

All of your CO2 gas will become a dissolved solid, result – a big drop in pressure. It is readily possible to collapse an FV because of the vacuum formed. The safe approach to manage this issue will depend on the size of the fermenter. Massive lager FV’s would need an air purge and CO2 monitoring. Smaller vessels can be managed by three x 10 second water sprays and leaving an inlet open during the initial caustic circulation. This worked fine on 5000 L FV’s with a 1 ½” being left open (and a short hose running to the drain). I have seen people leave the manways cracked open but this is dangerous in its own right as you’ll get hot caustic splashing into the work space – no thank you!

Inorganic soiling

In a small brewery you are most likely to see this in your hot liquor tank or in your casks. Here the aim is to solubilise the Ca / Mg salts with a suitable acid. The preferred option being phosphoric acid or a phosphoric / nitric mixture (NiPac B). This should be used at 1-4% and cold or warm, never above 50 C or it will fume. Again you’ll need a good water flush (see below) afterwards and this time litmus paper to check.

Biofilms

A less frequent task. If these are to be removed with CIP you would use your normal caustic solution (1-3%) but add to it some hydrogen peroxide (0.1-0.2%). However these often tend to build up in pipes where the flow rate is slow – such as the drain lines from your mash / lauter tun. Here the answer is mechanical effort! Sadly Murphy’s don’t sell elbow grease… I’ve had great success with a technique I used in the chemical industry called pigging. This is where an abrasive coated foam ‘pig’ is pushed down a line with air or liquid pressure. In the brew house a lower tech solution is required. Tie a foam scouring pad to a rope and pull through your lines until visual inspection shows them to be clean. The beauty, if there is one, with biofilm is that you can easily see it.

Sanitisation

Here there are a number of options, but a really good one is dilute peracetic acid. If used at 100-200 ppm it is not only an effective bactericide but will not need to be rinsed out of the vessel, simply drained. Another tip I learned is that most people can smell a dilute peracetic acid solution when it is above 75 ppm. So if you cannot smell it, either you have COVID or your solution is now too weak. Peracetic acid is another chemical you can buy readily from your local agricultural agent but again is something to be treated with respect as a concentrate and in accordance with your local risk assessment.

Flushing

Flush before you wash – that way the bulk of the soiling will be washed out and the potency of your cleaning chemicals will be preserved for multiple cycles.

Flush after you wash – Here you can work smart and save both time and water. Three ten second flushes will be a lot more effective than one 1-2 minute continuous spray down. The reason is all down to dilution (diluting by 90% three times (99.9%) is much better than diluting by 98% once). The pooling of liquor at the bottom of the vessel.

Need more advice?

If you buy your cleaning chemicals from a large supplier they are normally very happy to come and answer any of your questions. If you are a micro-brewery and this is not an option for you then contact me and I can help. Having worked in the chemical industry before I started brewing means I have a sound background in chemical safety and vessel cleaning methods.

When it came to running off the wort I had a new toy to play with. This was a first time I’d seen a Valentine Arm in the flesh, but what a nice addition it was. The subtly by which I could adjust the flow rate of wort out into the under back was fabulous. It was so much better that the ubiquitous butterfly valve you find on almost all mash tun outlets.

When it came to running off the wort I had a new toy to play with. This was a first time I’d seen a Valentine Arm in the flesh, but what a nice addition it was. The subtly by which I could adjust the flow rate of wort out into the under back was fabulous. It was so much better that the ubiquitous butterfly valve you find on almost all mash tun outlets. Five days later we were at 1010 and it was time for a

Five days later we were at 1010 and it was time for a